DA, observable consensus-free replication

DA, as a bridge to asynchronous verification, will be the bottleneck of the throughput of the entire Layer2 system. The rate of state update must be dynamically balanced with the throughput of DA. If the state update rate is always faster than DA, there will be a situation that Verifier cannot verify the state during the challenge period due to the absence of data in DA. Therefore, DAC has become a relatively relaxed implementation of DA, and has become the choice of many people:

We certainly hope that a DAC or something will break the performance shackles and still be fully secure as Layer2. Interestingly, we also realize that this is asking Layer1 to break out of its own shackles, so we have to loosen up some of the DA and Layer1 security. The most direct way is to reduce the network size and create a mini Blockchain, when the network is small enough, the DAC will be visible. However, such a way of thinking is the ripples of the impossible triangular vortex of Layer1, and does not take Layer2 as the core of the perspective. This is a direct result of the instinctive aversion to DAC. because it always comes across as a trust-dependent pseudo-blockchain.

Is it better to suffer in silence as the DA chain fails to keep up with the pace of execution? Or should we commit to DAC's secure black box? To be or not to be, that is the question.

Before answering yes or no, we need to go back to the origin of the question and examine whether we have asked a good question. In fact, the origin of the DA problem is not the DA itself, but its position in the Layer2 network.

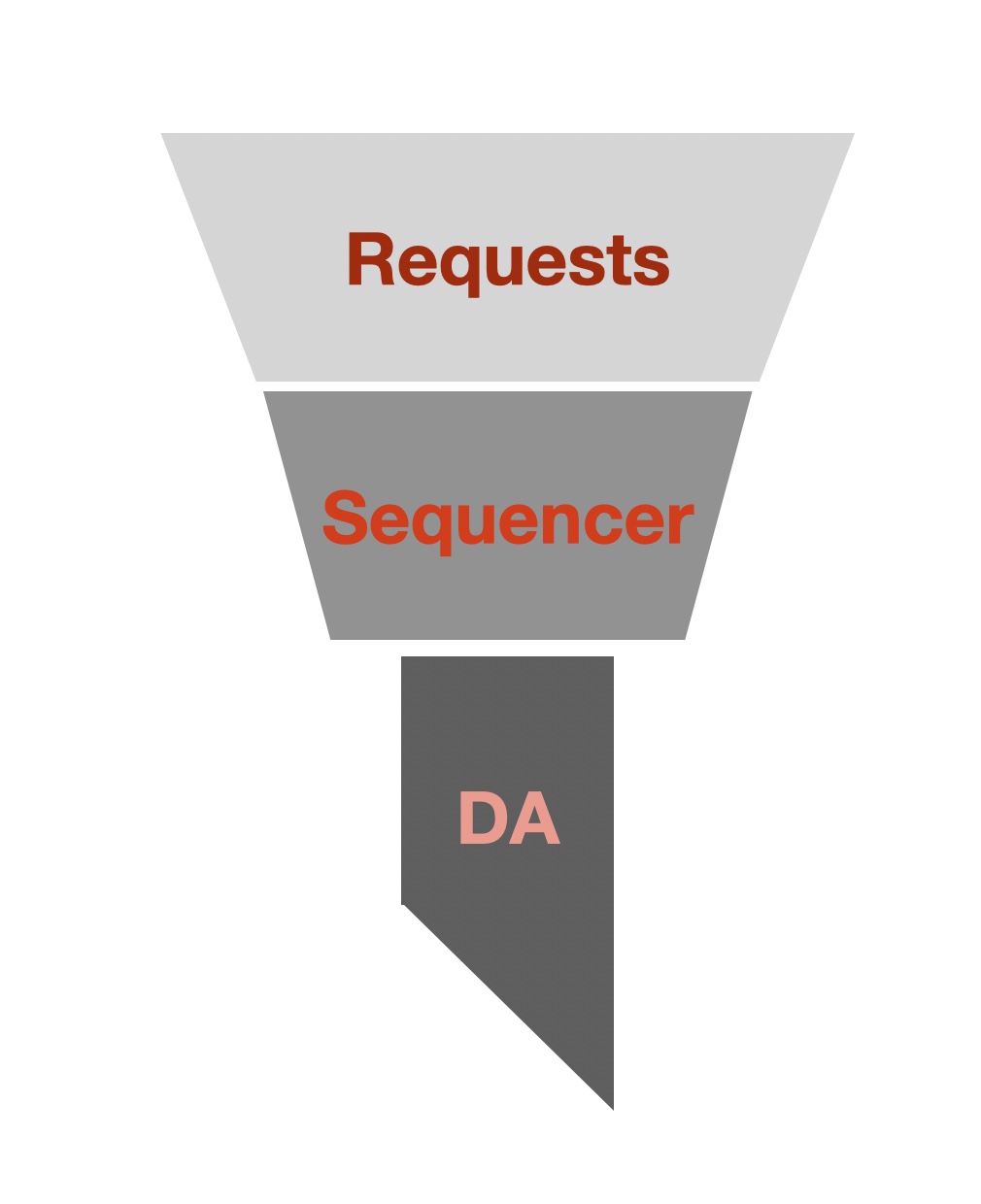

From a Layer2 perspective, let's look at the role of DA in the Layer2 standard model:

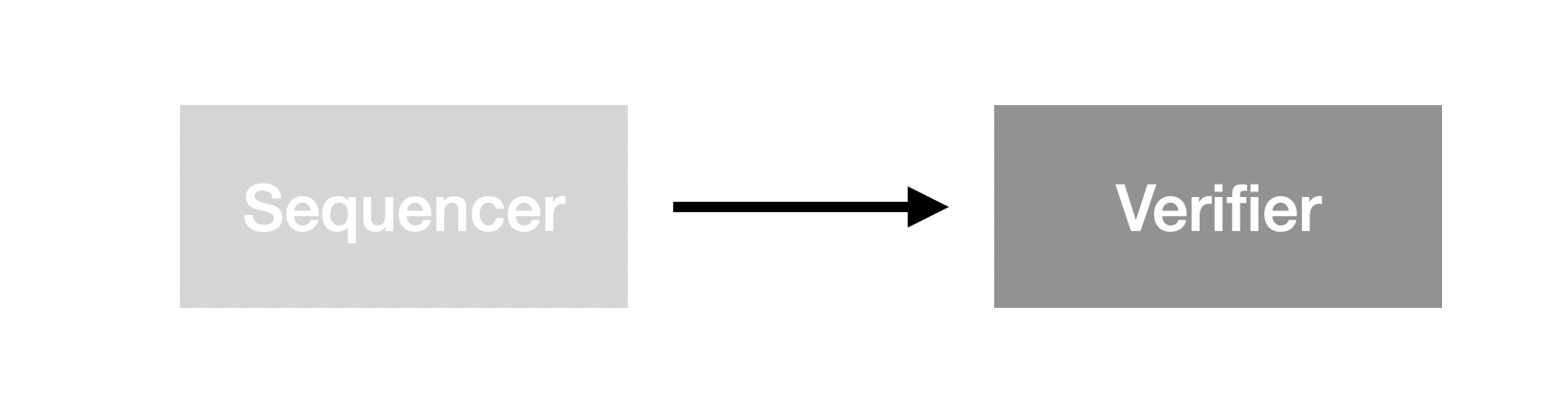

This is a sketch of the synchronization causality of Sequencer with Verifier, where the directed edges represent I/O causality. The output of the Sequencer is directly verified by the Verifier as input to the Verifier. This is also the basic model of on-chain verification. In the Layer2 network for scaling purpose, we can't guarantee strong enough instant verification, so we need DA to be the asynchronous communication bridge between Sequencer and Verifier:

This figure provides a clear picture of the first major design question about DA: do DA have decisions about the content of the data? In other words, does the DA need a consensus mechanism? The reason why this question is so salient here is that the constraints from Sequencer are often ignored in discussions of DA, and DA is treated as an isolated service, which leads to a design dilemma. In fact, the discussion of this issue is only complete when Sequencer is explicitly stated as the "cause" of DA. It is not difficult to realize that no matter how DA is designed, the consensus reached by its consensus is only the output of Sequencer in Layer1, so the consensus of DA itself is as insignificant as pouring a glass of water in the Pacific Ocean. Self-fulfillment is Layer1's invocation, requiring a large economic network to support its prophetic self-enhancement.

Happily, we bypassed a layer of consensus burden (DA). Unhappily, it validates the data based on another layer of a heavier consensus network (L1). Another "To be or not to be" problem. Again, it seems we are asking a direct question rather than a fundamental one.

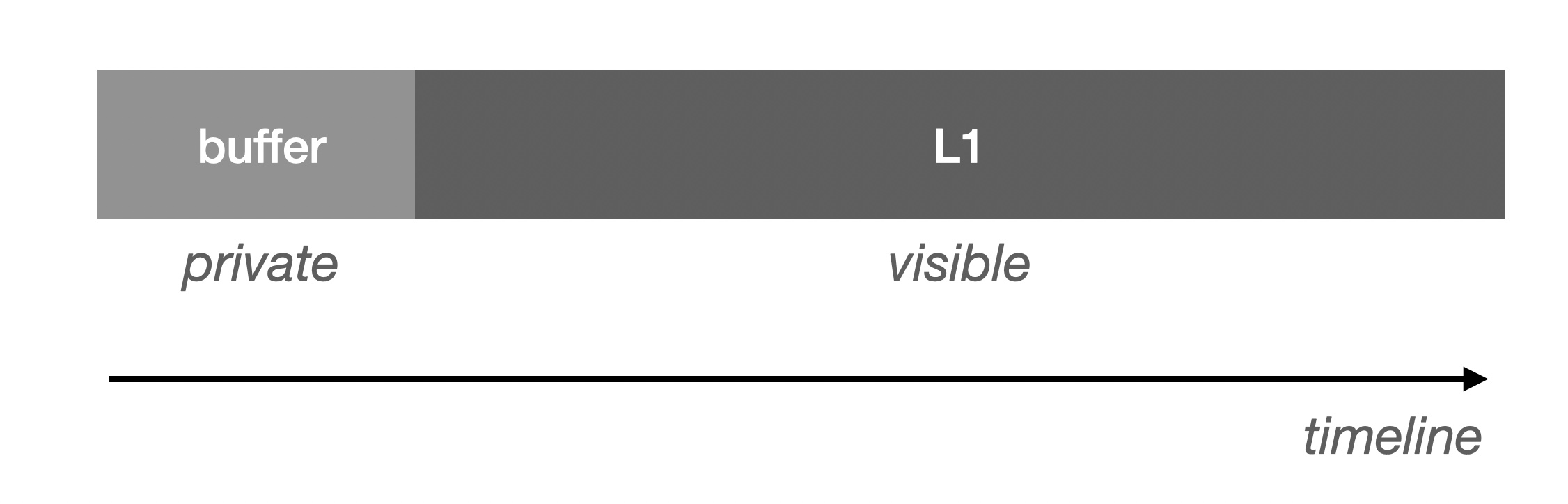

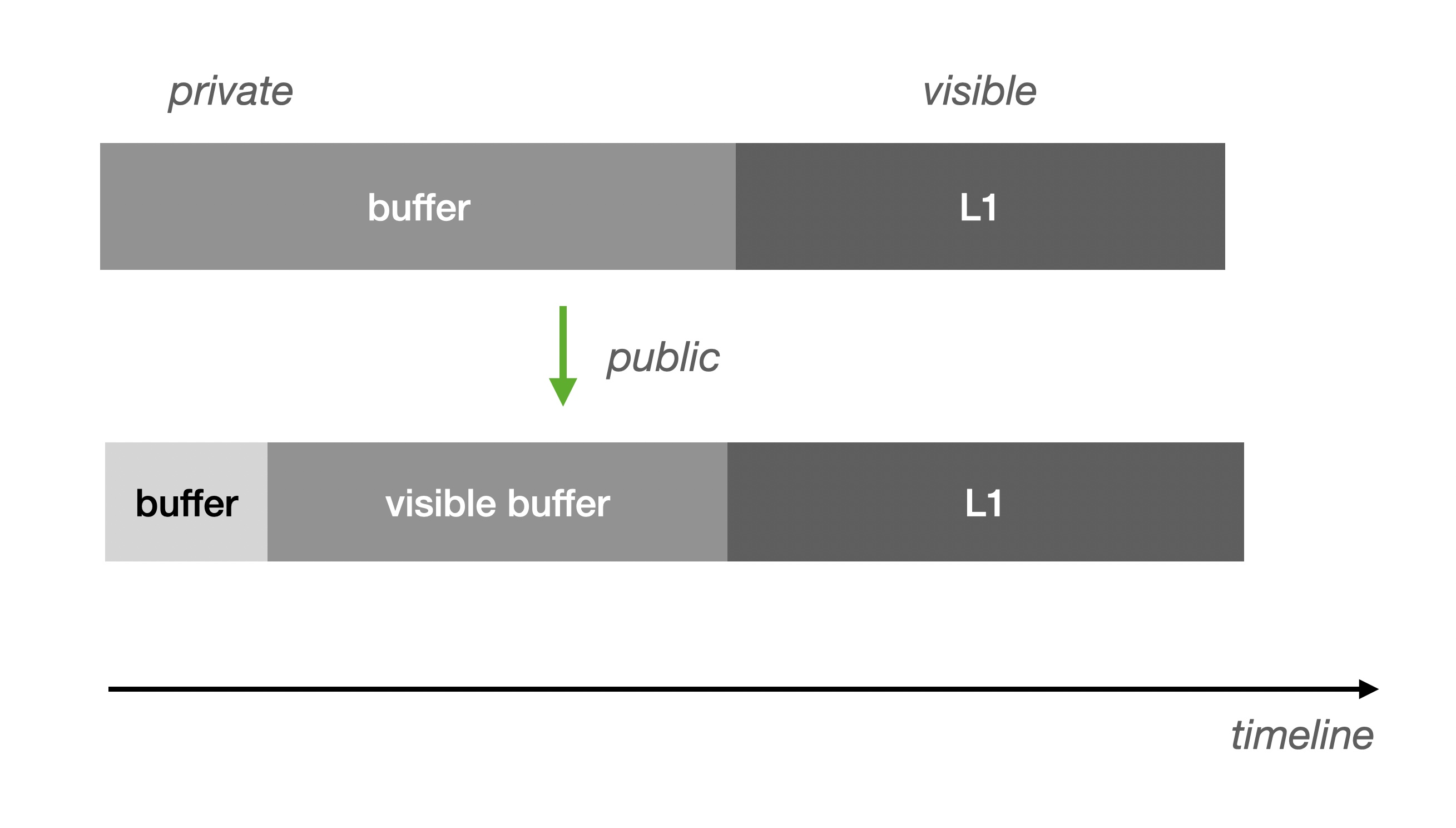

Since we are relying on L1 to validate the DA's data, we must trace the origin of the validation data on L1. Since blockchain calls/space are very expensive, typically we set up a buffer that Then write to L1 in a batch fashion (equivalent if DA is on L1):

It should be noted that invisibility implies a lack of causal binding. In the case of a Buffer, it is usually located in the L2 Sequencer, which is the part of the data that is not yet ready. If it is exposed directly to the public, the Verifier will not be able to utilize it directly because it may be volatile. The only window of certainty is when it's ready to be swiped into L1. At this point, the data obtained through the Buffer will wait until the L1 write is complete and can be verified.

Now it's easier to visualize why DA limits the throughput capacity of L2:

Since there is a speed difference between Buffer and L1, when there is no restriction on Buffer stacking, there is bound to be Buffer overflow, which will lead to DA not being able to write to L1 in time, and thus the Verifier will not be able to be verified on time. In order to avoid this situation, we have to do requests limiting.

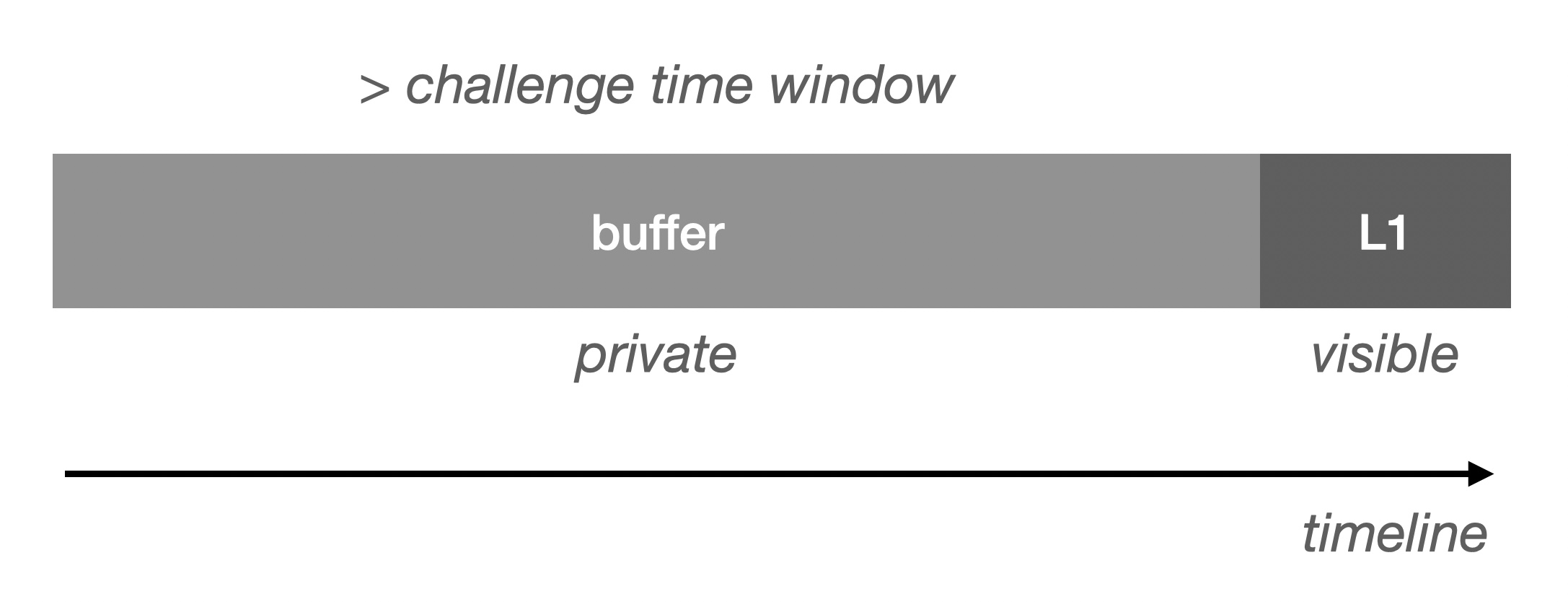

Just now we mentioned the deterministic time window of Buffer (verifiable), so we can expose this part, if this part of the data is large enough can greatly reduce the possibility of flow limiting:

Visible Buffer and Data Publication (more on the naming debate between Data Availability and Data Publication later) are equivalent in terms of Verifier support. However, this approach to improving throughput is not suitable for publishing data to L1. In addition, there is a need to compress the data digests, and we only need to write the root of the digests of a batch of Buffer Blocks to L1 to satisfy the verification requirement. Otherwise it would be ineffective and would still block at L1 for visibility.

Currently, we know:

- DA does not need consensus: it relies on L1 to provide data verification.

- DA needs Buffer: to reduce L1 resource consumption.

- DA needs Visible Buffer: improve validation efficiency.

- Premise that Visible Buffer and L1 Data Publication are equivalent but not identical: public data to non-L1 platforms and compress data digests. Otherwise, one would still need to wait for L1 blocking, being identical with Data Publication.

But functional equivalence is not the same as security equivalence. While we cannot achieve L1-equivalent security assumptions, we can try to achieve L2-equivalent security assumptions. We want this security assumption to be simple enough to state the upper and lower bounds in a single sentence, rather than exploiting the desire for certainty to peddle complex and grandiose prophecies. A security assumption that is easy to understand attracts more participants and thus has the opportunity to create security self-enhancement.

The counterpart to the L2 security assumption is our expectation:

Only one honest Visible Buffer node is required to guarantee security.

Naturally, we want the Visible Buffer to operate as decentralized as the Verifier by having different entities pledge it, and we now give the Visible Buffer a new name: Data Visibility.

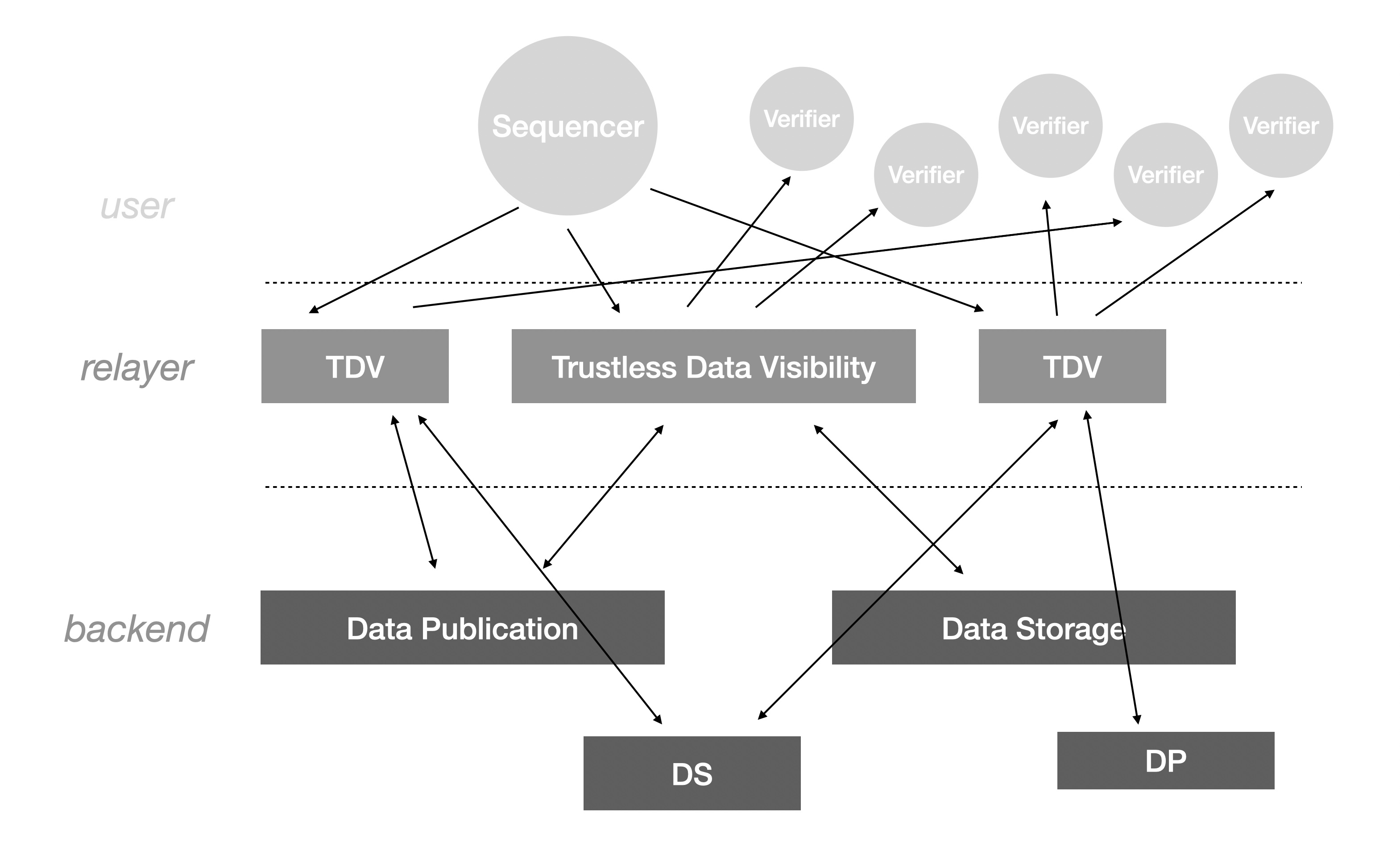

We categorize DA-related components into three layers from top to bottom:

- user: the user of the DA, including Sequencer and Verifier.

- relayer: the decentralized relay node of DA, the user-facing service consisting of Data Visibility.

- backend: the storage service that the realyer relies on, which may be Data Publication if the stored objects have only short-term read requirements, or Data Storage if the stored objects require long-term read requirements. The implementation depends on the relayer's consideration of revenue and quality of service.

For our part, we now need to roll up our sleeves, get our act together, and start analyzing in detail the specific issues facing the middle layer, Data Visibility (DV). As stateful storage, it must be ensured that it works honestly from an I/O perspective:

(1) Ensure that data is written and saved correctly (2) Ensure that reads are responsive (3) Ensure the integrity of the read response

Three iron curtains have opened up since then.

The First Iron Curtain: Proof of Persistence

Let's look at the first iron curtain of DV (Data Visibility), which is the equivalent of proving that the water coming out of a pipe came from its own reservoir or was pumped from somewhere else. This seemingly unsolvable problem is one that DV has to face, because water is H₂O in everywhere. This is because every piece of data in DV has open multi-node access redundancy, so as long as there is an honest node that holds that piece of data, every other node can forward a client read request.

The most serious cost of this problem is not in terms of unjust enrichment, but in terms of the reliability risk faced. This risk manifests itself in different ways in different forms of DV data distribution:

(1) Erasure Code-based striping: for k+m (k original data, m redundant data) strips with n nodes, the data is uniformly distributed. At least kn/(k+m) honest nodes are required to provide complete data. (2) Based on full replication distribution: n nodes each have a copy of the complete data. At least 1 honest node is required to provide complete data.

Let us go back to the problem of proving that "water is water" mentioned at the beginning of this subsection. In fact, water is not created out of thin air, it also has a cause. The process from the cause of water to the result of generating water can be called the state (change) distance. For example, we can easily prove that the water in front of me is not the snow water I collected from the Himalayas three seconds ago, because my speed is not enough for me to realize such a short state distance. Based on this bit of basic common sense, we can attempt to construct the proof now:

(1) the basic premise: the DV node received accurate data and responded to Sequencer's write request (2) the state distance to access the remote storage is much larger than the local storage

For (1) since Sequencer is the cause of the DV data, then Sequencer can hold two digests of the data, the first for end-to-end checksums and the second as the hash of the data stored on the DV. Since there is no way to know the hash value in advance, the DV would have to completely download the full amount of data and return the computed hash to the Sequencer for verification. The solutions to (1) are varied and need to be designed with the specific DV network architecture in mind. All that needs to be done is to avoid DV not performing the actual download.

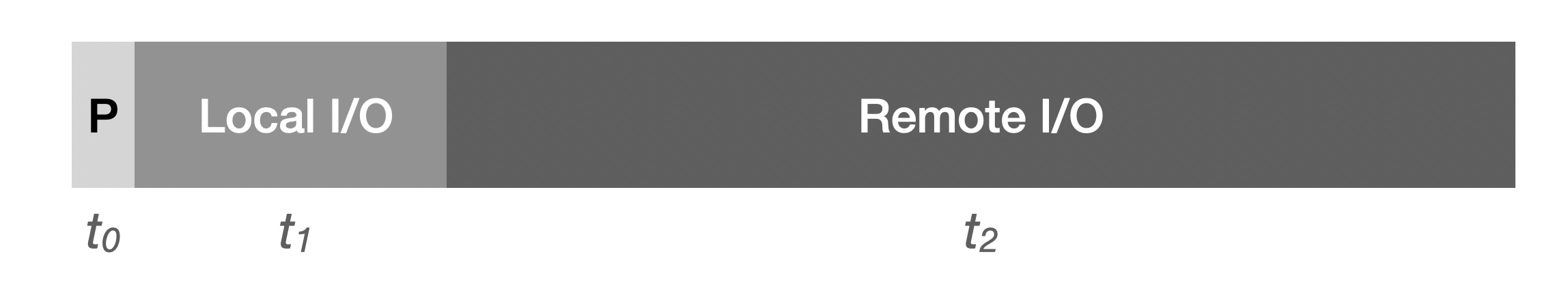

As for (2), the community has actually done a lot of interesting work, the essence of which is to provide state distance-based persistent proofs while minimizing the overhead of blockchain smart contracts:

We need the sum of t0 (proof generation time) and t1 (local I/O time) to be less than the proof submission deadline. To be clearly distinct from t2 (remote I/O), we need this sum to be as small as possible. This we can achieve by iterating a large number of random I/Os in the expectation that the network overhead caused by fragmented requests grows significantly. State distance as strong evidence (especially after multiple rounds) can be effective in identifying inaction of DV nodes. It is also possible to iterate the algorithm and dynamically tune the parameters to enhance the effectiveness in the future. However, it is important to realize that if all checks have to be performed through public chain contracts, their inefficiency will inevitably make them ineffective. This is why off-chain generation of proofs has become a popular option for many, such as utilizing Zero-knowledge.

In addition, we must be clear that DV is responsible for Layer2, so checks initiated at Layer2 are the right thing to do (don't forget that if Layer2 cheats, it will not be able to pass the fraud proof). To further improve the efficiency of checking in Optimistic Rollup, we can work with interactive proofs:

- the Sequencer slices the data into a fixed number of slices of a fixed size and forms a merkle tree(using 0 when size is not enough in calculation), where the root (hereafter object_root) will wait for the DV to return and then validate it

- the challenger generates a large range of slices (e.g., [0,256) bytes in slice 1) and composes a merkle tree from the list of ranges, which is seeded by the challenger's random numbers

- The challenger challenges a DV service provider with a random number seed via L2. If the challenged party meets the challenge period (e.g., seven days without being challenged), then the challenge is initiated.

- the challenged party generates a range list based on the random number seed, and will generate a merkle tree root within the time specified in the contract, otherwise it will be penalized

- the challenger uploads his merkle tree root, if there is no match. Both parties find the first unmatched range hash by binary lookup.

- both challenger and challenged submit the slices where the mismatched ranges are located, and the proof that the slices are in object_root.

- The contract verifies the proof of existence of the slice. Invalid proofs are penalized accordingly

Considering that the DV service provider may only be a decentralized relay node in the initial implementation, the actual storage may be completely remote, and the remote storage may not support range requests. The challenge mechanism will initially implement only the slicing and summarization algorithm functionality in preparation for future upgrades. In addition, the incentives and security assumptions of the challenger are basically the same as those of OP Rollup, so we will not repeat them here.

The Second Iron Curtain: No Response Attacks

The unresponsive attack is a manifestation of the unsolvable two-generals problem in DV, where a DV node can selectively respond to client requests while pretending to be unreachable. The premise of penalizing this type of behavior is that we have expectations about the availability of the DV node. That is, we have precise requirements for the availability of the DV node's services.

For Layer2, immediate large-scale read requests come from Verifier nodes, and Verifier, as the security line of defense for the Layer2 network, can naturally assume the responsibility of checking the availability of DVs. Otherwise, the Layer2 network is not established. Under this premise, it is acceptable for Verifiers to act as a relatively authoritative third party to deal with the two generals' problems.

Thus the most direct way to combat unresponsive attacks is through the role of Verifiers:

Verifiers request DVs by hiding the true request address, thus avoiding DVs from recognizing the request, and record the quality of the DV node's response. This data is periodically written to Layer2 as a tx for adjudication by the DAO. The DAO will vote on the service quality of the DVs, penalize the nodes that do not meet the conditions, reward the nodes that perform well, and realize the rotation of DV service providers.

On top of this, we can also provide smart contract version of non-response verification. That is, initiating a Layer2 transaction requires the non-responsive node to provide data within a certain period of time. One of the major problems with this approach is that it takes away from the "scene of the crime". This is fundamentally different from Verifier's direct involvement. The same party that initiates the request and collects the results of the request ensures a complete chain of causality, and there is no reason for a DV node not to respond to an on-chain contract that carries a direct penalty. A separate topic that can be extended here is the importance of circumstantial evidence. Returning to smart contract constraints, we could naturally also utilize Layer1 for a more authoritative challenge, but it is almost difficult to work with due to efficiency issues.

In short, detection of unresponsive attacks must recognize the time-space limitations.

The Third Iron Curtain: Wrong Response Attacks

There is a third key weapon of DV cheating that is easy to overlook because the problem behind it is so "silent": Silent Data Corruption is practically everywhere, but due to its low probability of occurrence, it's not easy to detect. It has caused countless losses throughout the history of the Internet. So how much of an impact does it have on the Web3 world, and in particular the Layer2 networks we're talking about?

Unlike Layer1, Layer2 networks lack synchronization verification, and silent errors start to show up. After all, how can you correct yourself when you don't even know you're wrong? The DV node can take advantage of this to disguise its malicious intent. It's perfectly fine to return an error response and say that it was just unfortunate enough to stumble upon a silent error, so how do you tell the difference between malice and innocence? It's not a good idea to beat all error responses to death, because silent errors are far more likely to occur than one might think!

As with dealing with unresponsive errors, we need to first establish quality of service expectations, in this case primarily the BER of network transmissions. The solution to this problem is well established, namely the ubiquitous error correction code. Within the error correction range, the maliciousness of the DV node is meaningless, and outside the error correction range, we consider the DV node to have subjectively cheated. The use of error-correcting code is inexpensive, and turning it on at any time does not cause a degradation in throughput efficiency.

Again, as in the case of non-response errors, the accident scene issue is involved here. Again, we can introduce Verifier to provide raw evidence of cheating by the DV node. The main reason why the direct determination of smart contracts does not work here is the same as above and will not be repeated.

The Violent Aesthetics Behind Data Visibility

We know that DVs are huge buffers for storage, and their ability to support bursty traffic growth determines the upper bound of the Layer2 network. At the same time, we don't always face such a deluge of data. Combining peaks and valleys, DVs have excess capacity. Then, slower storage can act as an asynchronous backup function. Our backups can even go beyond the surface continents. There's no reason why we can't sink historical data to the bottom of the ocean, or launch it into the sky - what's to stop us from doing that?

Again, because the DV service is homogeneous, anyone can serve data externally before they have joined the DV network, it doesn't require any licensing, it doesn't need to deal with other formations to understand the metadata organization and go through the complex process of synchronization. If it does better, the DAO will cheerfully welcome it in and replace the underperforming DV with it. market competition is very destructive to the rigid whitelisting model, and such violence is what I expect. Virtue is based on the ability to use violence, and without destructive power there can be no self-restraint, and virtue becomes a weak rhetorical statement, the glare of the sword of Damocles making people polite.

Appendix A: Data Availability, Data Publication, Data Visibility

DA has recently (although it actually commenced quite some time ago) been further clarified conceptually. Given its practical function, it would be more aptly referred to as DP (Data Publication), thereby clearly distinguishing it from permanent storage or Data Storage.

In my perspective, DA can entirely function as an abstraction layer for DP and DS (Data Storage). When our storage strategy is data publication, it manifests as DP, and when our strategy is permanent storage, it surfaces as DS. The concept of Data Visibility, as mentioned in this article, is an extension of the DA concept developed from an L2 viewpoint. Our concern lies with the visibility of data on L2, and we remain indifferent to whether its backend implementation is DP or DS.